A Drinker's Excuse

How my failure to buckle down in math classes set me up for drunken foolishness

I left high school with a diploma—and the necessary ingredients for addiction. A close look at my ACT scores revealed that I was on a bad path.

The raw numbers were not exactly the problem. It was the gap between the numbers that was the problem. My score on the English/Language Arts portion of the ACT put me somewhere in the 90th percentile.

But the Math/Science portion was dismal. My high school guidance counselor explained that the score meant I was functioning on 4th-5th grade level regarding numbers.

According to the test, I was functionally inumerate.

How did it get so bad?

Math was slightly less rewarding to me than reading. The slight difference in how rewarding each material was became amplified over my school years. Over time, I turned that slight preference for literature into a full-blown failure to launch into adulthood.

It would take a writer with the psychological insight of Doystoevky to do justice to my wretched inner roiling. He would write a novel entitled “Math and Literature” with me as the protagonist who devises a plan to kill my math instructor. [I would eventually be redeemed— like Raskolnikov—by a prostitute who embodies Christian virtues].

To save you from having to read a Russian novel, I’ll just give you this Functional Behavior Analysis to show you how my poor math scores came to be.

The main factors in my low math scores are my parents’ ineffective response to my low math scores and the fact that I was placed in school a year too early. My childhood illness—a heart defect—contributed to my parents’ ineffective response by making them unwilling to clamp down when necessary.

My childhood illness led to me being put in school too early. My parents rightly worried that a child who spent so much time interacting with doctors and nurses would not fit in with other children. So they rushed me into school when I would have benefited from another year of developmental maturation.

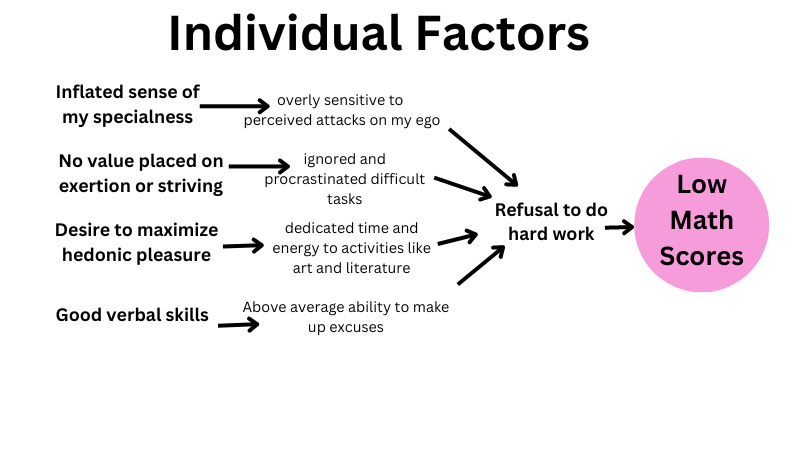

This chart shows the factors that contributed to my refusal to do hard work. My refusal to do hard work, combined with my parents’ ineffective responses to my poor grades, created an environment in which I could get through 12 years of private school and remain essentially innumerate.

To try or not to try, that is the question.

Failing math classes is very uncomfortable. Each test and quiz felt like chisel chipping away at my self-confidence. Yet the fear of buckling down and doing my homework was even greater than the discomfort of getting low math grades.

I didn’t understand this until much later, but buckling down was so unattractive to me because it might crush me.

Think about it. What if I gave 100% to my math class and still failed? Could I handle finding out that I was subpar?

I figured it was better to be suspected of being a low-performing math student than to try my best and prove it.

Good verbal skills + bad math skills + incredible ego = Walter Mitty

So, I developed an elaborate coping mechanism to deal with the daily frustration of receiving low math scores.

Using little more than a passing knowledge of Fascism and a misunderstanding of the brain’s right and left hemispheres, I developed a global value system that converted my academic failure into a badge of honor.

I determined that math was a left-brained activity, which according to my misunderstanding of neuroscience meant that it was boring, lifeless, and robotic. The left brain—which I chose not to develop—was full of people like Hitler and my math teachers. People who valued numbers over humans.

Left-brained people were cruel and petty. They would mark an entire math problem wrong because I failed to perform one little arithmetic function properly. Imagine getting 10 points off a quiz simply because you failed to carry the 3 over to the tens column. My Literature teachers would never grade in such a reductive way. They appreciated that I ressonated with John Donne’s “I struck the board and cried no more”, even when I couldn’t spell “resonated”.

Anyone who willingly used or taught mathematical skills was the kind of person who Ralph Nader would refer to as a “bean counter”. Bean counters would sentence a million Americans to a preventable death instead of forking out the cash for a gas tank that wouldn’t explode on contact.

In contrast to the left brain, the right side of the brain was where all the creativity was. Einstein, Van Gogh, DaVinci, and other people just like me were all “right-brained”. We saw the world intuitively and thought outside the box. We had principles derived from the great works of literature, and we would never allow unsafe vehicles off the assembly line. Literature majors were kind, eccentric, and charmingly bad with numbers.

I relied on this coping mechanism of mine until it became a full-blown worldview. I took everything hard, everything that required effort, everything that challenged me, and lumped it in with Fascism, brutality, and gulags.

My completely imaginary sense of self-importance made me the Walter Mitty of Math class.

When I got a 60% on a math exam, it wasn’t a poor score—it was validation that I had not succumbed to the machine!

Predictable results

My vision for how the world worked was so stupendously wrong that it made me incapable of gainful employment.

In fact, I couldn’t pass the remedial math classes I was required to take in college. This meant that I couldn’t even enroll in the math classes needed to graduate. If I wanted to become an English professor, Math stood in my way.

So there I was. A huge ego with nothing to back it up. A desire to confront Fascism and an inability to multiply fractions. My only options were to

completely reorder my vision of the world and buckle down with math books until I reached basic competency

drink until nothing mattered.

I chose to drink.

Epilogue

I eventually overcame my aversion to math. I passed the remedial math classes and got an A in Pre-Calculus. I graduated from college. I scored in the 83rd percentile on the math portion of the GRE, an entrance exam for graduate school. I took advanced classes in statistics in graduate school. I even taught 8th-grade algebra for a semester. It turns out that when I applied myself, I was not horrible at math. I just wasn’t as brilliant as I thought I should be given how much stroking my ego demanded. My pathway out of innumeracy and dismal math scores became a template for later battles with alcohol, anxiety, and anger.

In a later post, I’ll share how I got out of the hole I dug for myself. And perhaps I’ll even share how digging myself out of the hole was an initial step toward becoming a social conservative.