To Get Mad or Not Get Mad

Why expressing anger is often unwarranted

Candice burst into the group therapy room in a panic. But when she looked at the wall clock, she smiled and sighed in relief. She hadn’t actually arrived late to her court-ordered group therapy for substance abuse. In fact, she was 3 minutes early.

I saw scenes like this one with Candice repeat themselves dozens of times with different clients during my time as a court-ordered substance abuse therapist. The reason people like Candice panicked was that being turned away for tardiness could result in severe consequences from their probation officer. In the best-case scenario, arriving late might mean a client would have to make up the class, essentially adding another week of court-imposed group sessions. But, in some cases, excessive tardiness could even mean being sent back to jail or prison.

Thinking you are late as an object lesson

I would use these near-tardy experiences to help explain that the human brain often can’t distinguish thoughts from reality, and that this quirk of cognition could put us at risk of relapse. As the person who just ran into a group session in a panic could attest, they experienced all the internal emotional turmoil of being sent back to prison, just because they thought it would happen. The brain didn’t take a wait-and-see approach before deciding to panic. Instead, it went into overdrive, telling itself, “You really screwed up this time,” and imagining all kinds of unpleasant interactions with family, probation officers, and the judge.

Yet, the panic was completely unwarranted. They were not, in fact, late.

Learning that thoughts and emotions can be unreliable is an important lesson for people in recovery. Too often, strong emotions can result in relapse. Strong emotions can lead to a sort of self-pitying form of nihilism that makes people think things like, “Why not drink? This staying sober stuff is too hard. Plus, my Probation Officer has it in for me. Might as well get faded before they lock me up again.”

Not Shakespeare again

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the best tools a therapist can use when it comes to helping people in recovery learn to manage strong emotions. CBT’s take on the role of cognition is often confused with something Hamlet said in Act II, Scene II: “Nothing is either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” Hamlet’s point is that something can be neutral until you add a meaning to it. While that can be part of what CBT teaches, there is an even more essential lesson at the heart of CBT. CBT teaches that when emotions are strong, it is often due to thinking errors. Because of this, CBT teaches that thoughts should not be automatically believed; they should be put to the test to see if they are helpful or accurate. In CBT, thoughts and emotions are signals to begin a level-headed fact-finding mission.

Whereas Hamlet suggests that there is no meaning to an experience until we ascribe one it, CBT teaches something more like, “19 My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, 20 because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires.” In other words, the times when we are most upset are often times when we don’t really understand what has happened.

To help clients understand this point, I would sometimes ask them to think of a time they got really mad about something, but later found out the thing they were so mad about wasn’t worth the bother. One woman explained that she got into a shouting match with her sister over a blouse she couldn’t find. She assumed the sister had stolen it. But that’s not what happened. Instead, she remembered a few days later that it had been left in her own backpack.

But because the woman was not quick to listen and slow to speak, both she and her sister experienced all the unpleasant emotional upset of an event that never happened. A thought made them angry. If they had interrogated the thought, the fight might have been avoided.

Automatically Mad

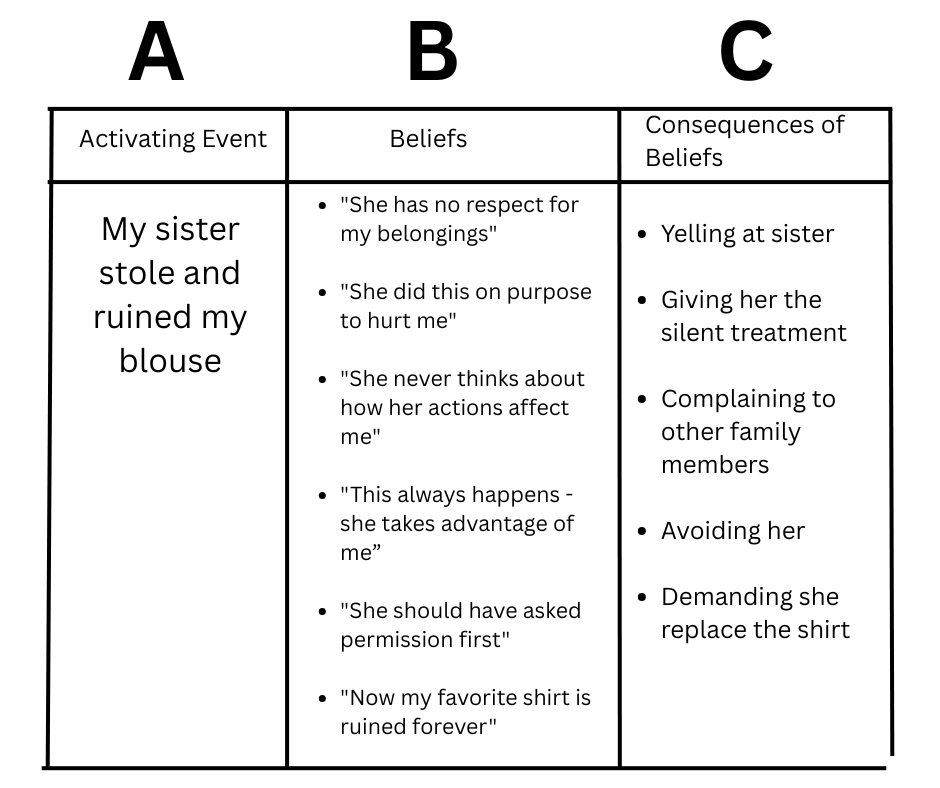

But to really see the power of CBT, let’s imagine an even worse situation. Say the shirt had been stolen, worn, and ruined by the sister. We can call this scenario A=Activating Event. What often follows an Activating Event is a set of automatic thoughts, we can call, B=Beliefs. These automatic thoughts, if uncritically accepted, will often lead to some unhelpful behavior that can call C-Consequences of Beliefs. See the matrix below.

Come, let us reason together

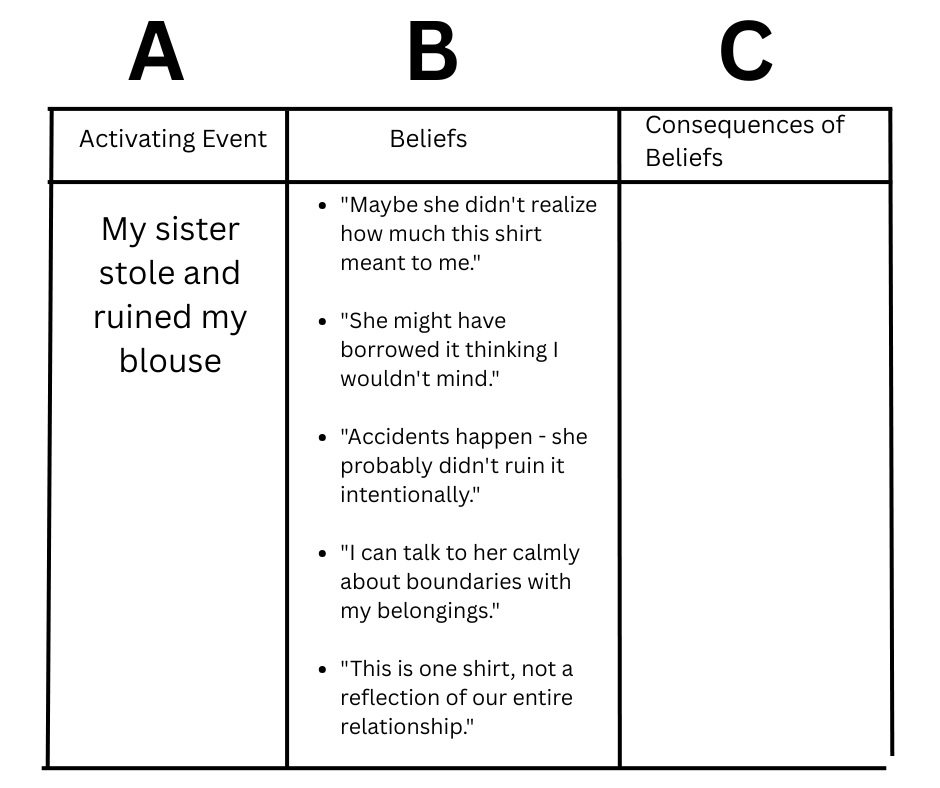

Therapists using CBT will teach clients to hold off on any action until they consider some alternative beliefs. These alternative beliefs often lower the level of anger. What do you think would be in the box labeled “C-Consequences” if the client thought these thoughts instead of the previous ones?

The behavior based on this second set of beliefs would likely be more helpful than the behavior based on the first. The strength of the emotional response would also be more manageable, and less likely to provoke a relapse.

Don’t confuse this with catharsis.

Once a person has arrived at a more helpful set of beliefs, they can take some next steps. The next steps might involve direct communication using “I statements.” I can see where “using ‘I’ statements” could be confused with catharsis. After all, an “I-statement” might involve explaining why taking the shirt was problematic. “I-statements” might also involve saying how it felt to have the shirt stolen and ruined.

But using “I statements” is not the same as “expressing yourself” or “getting the big emotions out.” In fact, using “I statements” requires the client to contain her immediate emotional reaction and state things in a calm, non-inflammatory tone. “I statements” don’t work because they purge the speaker of toxic emotions; they work because they communicate in a calm, adult-like manner that lowers the likelihood the listener will react aggressively. This calm, controlled way of speaking, then, allows for productive activities like boundary-setting or problem-solving—or even apologies.

Whispering words of wisdom

CBT also teaches that there are times when it is best just to let it be. I wrote a post about a time when a fellow Prison chaplain ignored a rude and hostile inmate. I believe he made the correct decision and avoided an escalating conflict that might have required the involvement of prison guards to put an end to.

The Bible says, “Love covers a multitude of sins.” I take that to mean that sometimes we ignore it when someone offends us; perhaps we show forbearance or patience. In the case of the two sisters, letting it go might be the best scenario if the offending sister lacks impulse control or if she has a serious illness. Maybe one or both of the sisters are moving out soon, and the shirt problem won’t be an issue when they aren’t living together. There are lots of reasons to “let it be.”

Letting it be might make you a doormat. That’s true. But for many people in recovery, being a doormat isn’t the issue. Their problem is that they are slaves to expressing emotions—often with their fists. I can’t tell you how many prison conflicts are over some absolutely ridiculous “slight” or “offence.” What’s worse is that these silly situations can quickly escalate to dangerous levels of rage and violence.

I’ve been saddened on many occasions as I learn about someone who put their release time or their sobriety at risk due to a Pavlovian response to a perceived wrong.

As a therapist, I tried to teach that emotions and thoughts are often false alarms. The best course of action for many in recovery is to calmly investigate the source of the alarm before deciding how to handle it.

In a future post, I want to explain how Christianity goes beyond anything imagined by CBT and offers something deeper and more transformational. But for now, I’ll just leave you with this verse, which describes how Jesus approached situations that would lead most of us to smolder with rage and ignite overwhelming urges to take revenge.

When they hurled their insults at him, he did not retaliate; when he suffered, he made no threats. Instead, he entrusted himself to him who judges justly. 1 Peter 2:23

If you like the idea of insights like these being shared with people in recovery, Resilient Recovery might be precisely the kind of ministry you’d like to support financially.

As one Resilient attendee recently said, “I come here because it helps me understand myself better.”