Not too long ago, in a Bible study at the prison, an inmate waffled back and forth on whether she could handle social drinking when she is released in three years. It’s the kind of thing you have to be ready for if you are going to work with people in recovery.

The obvious answer to her dilemma is, “Don’t. Under any circumstances. Drink. Ever.”

But in situations like this one, where a person is waffling, it’s better not to say the obvious part out loud.

Within minutes, she contradicted a half dozen times.

I have this idea that when I get out of here, I am going to kick back and have some beers. Like, I just know that my real problem was Meth and kicking back will be cool. But, that’s nuts, isn’t it? I mean. I can’t drink alcohol, right? I need a clear head. And I need to do sober stuff. Some of that sober stuff is what’s up, Jonker.

She reminded me of a person frowning at a mole and asking a friend, “Do you think I should get this checked? It’s probably nothing, right? Just ignore it for now?”

It was as if she wanted me to look her in the eye and tell her that her plan was the dumbest thing I had ever heard of. And I could easily have gone that route. I could have given her some very sane advice—reminded her about how early she started abusing substances. How far she descended. How there is a pattern of substance abuse in her family, suggesting a genetic vulnerability. I could have mentioned that substance use led to her crime, or on a more positive note, I could have reminded her of all the things she says she wants to accomplish when she leaves. . . Any of those comments would have been correct and wise.

Instead, I wanted her to supply the reasons. So, I employed a straightforward technique designed to help individuals develop their own motivation for making a change. It’s called a double-sided reflection. I just repeated what she said, but in slightly different words, making sure the smart part was at the end of the sentence: “It sounds like you are on the fence. Part of you thinks you will drink when you leave here, and part of you thinks you shouldn’t drink when you leave.”

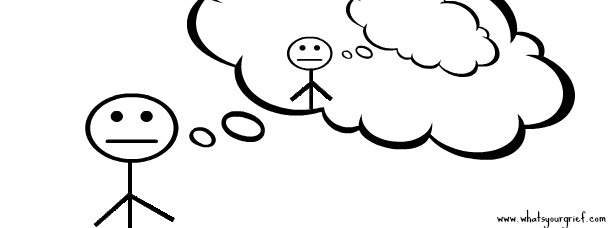

She agreed. And for the next two or three minutes, she continued to have a meta-moment, in which she thought about the thoughts she was having.

When it seemed like she was almost done, I said, “Well, you are conflicted. But, you have the next three years to make a firm decision about what to do.”

A few weeks later, at the end-of-the-Bible-study celebration, she put down her slice of pizza and made a surprising announcement. “I want to say something, Chaplain. You really helped me decide not to drink when I leave here. I have been nursing this idea that when I leave here, I can go back to getting drunk. That was insane. . . what was I thinking? Thanks for talking me out of that.”

Of course, the irony is that I specifically avoided talking her out of the idea.

Why not give helpful advice

There are two main reasons not to make a person’s arguments for them. First, arguing with someone can cause reactivity, a sciency word for getting your hackles up. And when that happens, people often strengthen their resolve to do the opposite of what has been suggested. At heart, we’re all toddlers with a reflex to say, “Me, do it!” when someone offers help.

Second, it’s important to let people in recovery practice making decisions. Dr Lance Dodes, a retired Harvard Psychiatry professor, believes addiction results from poor problem-solving skills. He tells the story of a man who became frustrated after forgetting where he parked his car in a new city. The experience felt intolerable until he decided to pop into a bar and put an end to several months of sobriety. Although it did nothing to solve his dilemma, it felt like he had made a decision.

I’ve seen this scenario play out recently with a guy we can call Pete. Pete was doing great in his recovery. He was discharged from his group home and landed a job. However, on his first day of work, he realized that the job location was too far away from his transitional housing to be a viable option. Almost on autopilot, he went to the convenience store and got a beer. Was it a good idea? No, but it relieved the tension he felt about what to do next. When overwhelmed, any step, even a dumb one, seems like a solution.

Now he is starting over at what feels like the very beginning.

As you can see, you might argue someone out of one bad decision. But, you can’t ever be there to intervene in every decisional crisis a recovering addict will face. If they are going to stay sober when your back is turned, they’ve got to build up their tolerance for frustration and learn to make hundreds of good decisions on their own.

Me-do-it-ism is probably healthy

For people like the waffling inmate and Pete, the most persuasive argument you’ll ever give is the one you kept to yourself. Let them talk. Let them hear themselves out loud. Let them practice sorting through the options before they land on a solution, because they need to improve at solving problems on their own if they ever want to stay sober.

Perhaps a bonus reason to keep quiet when a person in recovery is debating between an obviously good choice and an obviously bad one is that any argument they come up with will be more persuasive than yours, if only because it came from their own mouth. Reams of psychological research support the idea that we feel compelled to stand by our own voluntary, public utterances.

If a person in recovery lands on a dumb choice, it can be painful to watch, I don’t deny it. However, if we swoop in like helicopters to save them every time they battle crazy thoughts, our work will truly never end, and they’ll never learn to become better problem solvers.

Celebrate good times, come on!

On those glorious occasions when they do make a good decision, it’s time to celebrate. Inwardly, though. You don’t want your celebration to make them feel like they are losing their autonomy, or that the only good choice is the one we were hoping they would make.

This is how I celebrated when the inmate tried to congratulate me for her decision not to drink when she is released. I smiled and said, “You had a big decision to make, and it sounds like you’ve made a choice you can be proud of.”

It’s almost the exact same words someone told me 10+ years ago when I laid out my drinking pattern for them and asked them if they thought I was an alcoholic and should quit drinking. We were setting up for a meeting, and he set down the table we were carrying together to emphasize his point. He said, “I don’t know if you are an alcoholic or not. But, if you end up quitting, I think it will be a decision you can be very proud of.” I still remember it 10 years later. Other than allowing Maria to make an honest man out of me through marriage, it was the best decision of my life. Thanks, Paul!

Back to the inmate

Knowing that this particular inmate began smoking Meth with her mother when she was just 13 years old, I know that nothing about sobriety is going to be intuitive to her. She is going to have to consciously make hundreds of decisions that most of us can navigate in our sleep. But, at least she has this one nailed down. And keeping my mouth shut was my best contribution to her success.

Want to give even more? You can make a direct donation to our ministry.