The Question that Requires Priests and Doctors to Answer

Why it's so hard to know if a program works.

People want to know if a particular recovery program “works.” The correct answer to that question is, in nearly all cases, “Not sure.”

You don’t have to obtain an advanced research degree to see why it is so difficult to determine if a program works. This post will show that a simple thought experiment can demonstrate why almost no one actually conducts high-quality outcome studies.

People often ask if my ministry is effective.

What are the stats?

What percent of people get sober?

Do you have any outcome data?

Will the Stay in Touch Study prove that Resilient works?

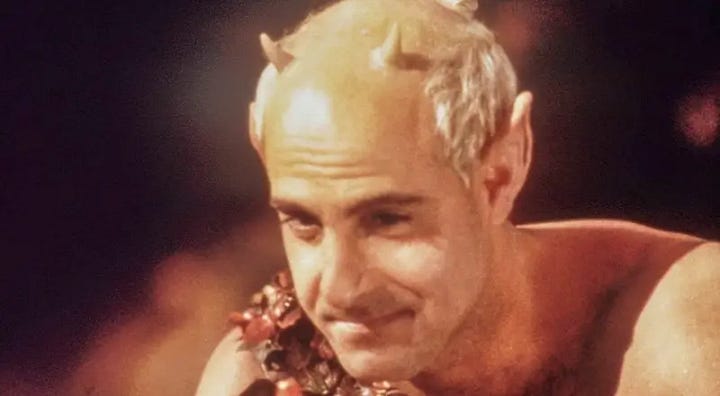

It’s an understandable line of questioning. Volunteers, program directors, and donors all have reasons to want answers to the questions above. But in my experience, these are very hard questions to answer. When people ask these types of questions, the last sentence from Philip Larkin’s poem “Days” always comes to mind.

Although answering the question of Resilient Recovery’s effectiveness might not be quite as difficult as answering where people could live if not in days, it is still way more complicated than people assume. It’s so complicated that you don’t even want to know (what it takes).

—But, imma ‘bout ta tell ya, anyway.

Vitamins for example

To see how difficult it is to determine if something “works,” imagine you want to find out if taking vitamin E will improve cardiovascular health outcomes. Here is why the cost of a no-frills study with only a few participants starts in the millions of dollars.

Developing the protocol and writing the grants necessary to conduct the research requires a team of highly trained scientists and graduate students. They don’t come cheap.

Recruiting people to be in your study is costly. The recruitment protocol needs to attract people from every walk of life. It needs to attract enough participants to have vitamin and non-vitamin groups.

Screening for eligibility. Background information and demographics must be obtained. Medical examinations must be completed to establish baselines and screen out people with disqualifying conditions.

Assuring compliance. To make sure people actually take the vitamins requires that you observe them taking the pills. This is costly and time-consuming.

Retaining participants and avoiding dropout.

Doctors and lab results. You’ll need good-quality assessments of health throughout the study.

Collecting, storing, and analyzing data is costly.

Time. The study would take about 20 years to determine if the vitamin group fared any better than the placebo group.

So, does Vitamin E reduce cardiovascular problems? Just give me 20 years and a few million dollars, and I’ll get back to you.

Why programs can be even harder to evaluate

Whether taking vitamins improves cardiovascular outcomes is a hard question to answer. But testing a program like Resilient Recovery, a parenting class, or Alcoholics Anonymous is even harder. That’s because a program isn’t an organic compound with easily definable characteristics that you can deliver identically to each participant. In the case of a program, every interaction, side conversation, or interruption introduces variability. And variability is the enemy of drawing conclusions.

Programs are less like organic compounds than they are like scripts for a play. The script gives direction and instructions, but no two productions of a play are ever the same. Think about all the productions of Shakespeare’s A Mid-Summer’s Night Dream. Branagh, Olivier, or your local community theater—something as simple as the character puck will be incredibly different from one play to the next.

Or imagine four college professors teaching an introduction to psychology class using the same textbook. Even if the university attempts to standardize the course, each professor’s personality will shine through, and each cohort of students will cause the course to have a unique flavor.

If productions of Shakespeare and Intro to Psychology classes vary greatly, imagine the experiences of people who attend a Resilient Recovery group run by me, Pastor Dan, Liz S, Verdell, or Laura. In practice, each group is as different as one marriage is to another.

Think of the controls and protocols that would need to be in place to ensure that study participants were getting something approximating the same Resilient Group.

Weeks of training, role-playing, and rehearsing

Scripts for what to say and how to conduct the sessions

Training on how to handle disruptions and questions

Workbooks that are costly to write and publish

Video recording of sessions

Coaches who review sessions and provide feedback to the leaders

The final problem with answering the question of whether a program really “works” is the problem of generalizability. Sure. You might be able to demonstrate that with tight controls and rigorously trained staff, your program works as intended. But, no one outside of the research environment is ever going to conduct the program with the same vigor and enthusiasm as the creator of the program.

The federal government used to host a website that had the ambitious goal of promoting the use of programs that have gone through the arduous and expensive process of conducting outcome studies. The National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices had a nifty rating system to grade the quantity and quality of the research for each evidence-based program or practice.

Yet nearly no one used those programs. The cost of implementation was prohibitive—too much training and oversight was necessary. And the materials were often proprietary and expensive.

In addition to the hassle and cost of using evidence-based programs, practitioners often felt the programs did not address the specific issues that plagued their unique community or school. It was the old Ivory Tower problem. Practitioners felt that pointy-headed academics were disconnected from the day-to-day realities of social work.

On the front lines, social work soldiers didn’t use the programs as intended by their academic creators. Instead, they built Frankenprograms made from the limbs and organs of many programs, often with a generous heaping of the social workers’ personal 2 cents.

So, does Resilient Recovery work? Ah, solving that question brings the priest and the doctor in their long coats running over the fields.

![Poem] Days by Philip Larkin : r/Poetry Poem] Days by Philip Larkin : r/Poetry](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Feaca4811-2fb5-4aaa-ae9b-b4c803fc222f_578x531.jpeg)