Three Reasons to Leave Stigma Alone

Or stigma may have been unfairly stigmatized

Government agencies and mental health advocates alike seem to agree that stamping stigma is obviously the correct thing to do. A lot of resources have been poured into combating stigma and making it more socially acceptable to have a mental illness and to seek treatment for it.

But, as your favorite crumudgeon, I am going to cross my arms and shake my head, “No,” instead of letting myself be swayed by the general consensus. In this post, I will give three counterintuitive arguments regarding stigma.

Removing stigma may usher in another set of problems.

There are times when stigma can be healthy and life-saving.

And even if stigma is making a problem worse, it’s almost never the first place I’d begin to fix the issue.

Read on to see what I mean.

Maybe we need some stigma?

I once had a very wise therapy teacher who would often repeat, “There are pros and cons to EVERYTHING.” This phrase would annoy many of his students who were convinced that there was always a clean and correct answer to clinical problems, an answer that was all upside and no downside. But in my 30 years of trying to help people—I have see the wisdom of his words proved over and over again. Every psychological solution carries some risks. In that way, psychological solutions are no different from pharmaceutical drugs—there are always downsides and side effects.

It may seem hard to believe that rooting out stigma could have a downside. But, before we completely eradicate stigma, we might want to consider Chesterton’s Fence. G.K. Chesterton, the Catholic thinker and writer, believed that we should not remove a time-honored feature of society until we understand why our ancestors put it in place. To make his point, he told this parable:

There exists[. . .] let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

For Chesterton, the wisest course of action is to leave a thing in place until we understand the function of that thing. I suspect he may have been reluctant to tear down stigma until he understood why it had developed in the first place and what function it might serve for society.

The internet may provide us with a glimpse into why society has erected a gate called “stigma” around mental health treatment. On the web, you can see what happens to young people when the stigma surrounding mental illness is completely removed. On social media sites, influencers describe their psychological struggles in detail. And while this may seem freeing, it has led to an uptick in inaccurate self-diagnosis for multiple mental health disorders, including disorders that are only caused by neurological issues, like Tourette’s Syndrome. Claude AI has this to say about the phenomenon:

“This phenomenon represents a form of sociogenic illness—the rapid spread of symptoms or behaviors through social groups via psychological rather than biological mechanisms”

It turns out that when you remove the stigma around diagnoses, one thing that happens is that teens start to mimic the symptoms of mental disorders as a path to a meaningful identity.

Something else happens when stigma is removed. In our attempt to normalize mental illness, we actually end up labeling human idiosyncrasies as medical issues. Writer Freya India has written an excellent Substack piece on this topic. She writes:

Anything too human—every habit, every eccentricity, every feeling too strong—has to be labelled and explained. And this inevitably expands over time, encompassing more and more of us, until nobody is normal. Some say young people are making their disorders their whole personality. No; it’s worse than that. Now they are being taught that their normal personality is a disorder. According to a 2024 survey, 72% of Gen Z girls said that “mental health challenges are an important part of my identity.” Only 27% of Boomer men said the same.

As my wise teacher said, there are pros and cons to everything. When he said this, he may have been channeling economist Thomas Sowell who famously said, “there are no solutions, only trade-offs.” Removing stigma may be the right thing to do, but it is not without some pernicious side effects.

Healthy and life-saving

In some cases, stigmatizing a behavior may save lives. Mothers Against Drunk Driving is an example of an organization that wielded stigma in a healthy and life-saving way. A behavior that was once considered silly, the object of comic relief in procedural cop shows, or shown without any discernible shame in movies like “It’s a Wonderful Life”, soon became very socially unacceptable through MADD’s advocacy. Here’s just one example of Americans’ views prior to MADD’s advocacy:

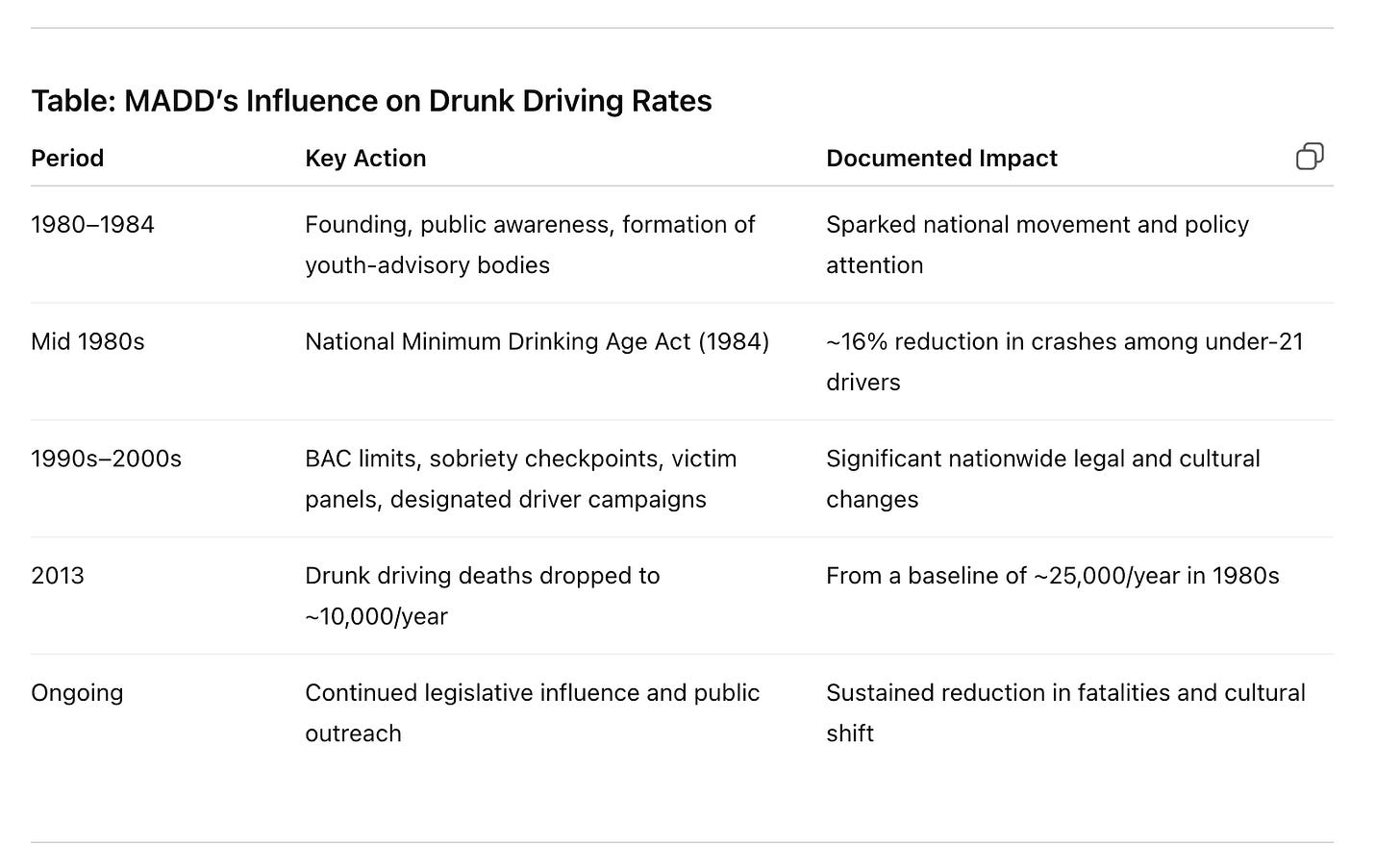

No doubt, much of the change was the result of harsher policies and enforcement. But the political will to enact harsher policy and enforcement was made possible because MADD stigmatized drunk driving. My friend ChatGPT organized this nifty table documenting MADD’s impact.

In the case of substance abuse, stigma could be a motivator to get free from an addiction. In city after city, the evidence suggests that a progressive and affirming attitude toward substance use increases substance use and the problems associated with substance use. Rates of crime and overdoses surge. Rather than emboldening people to seek treatment, reduced stigma emboldens people to increase their substance use.

Stigma isn’t a driver I would choose

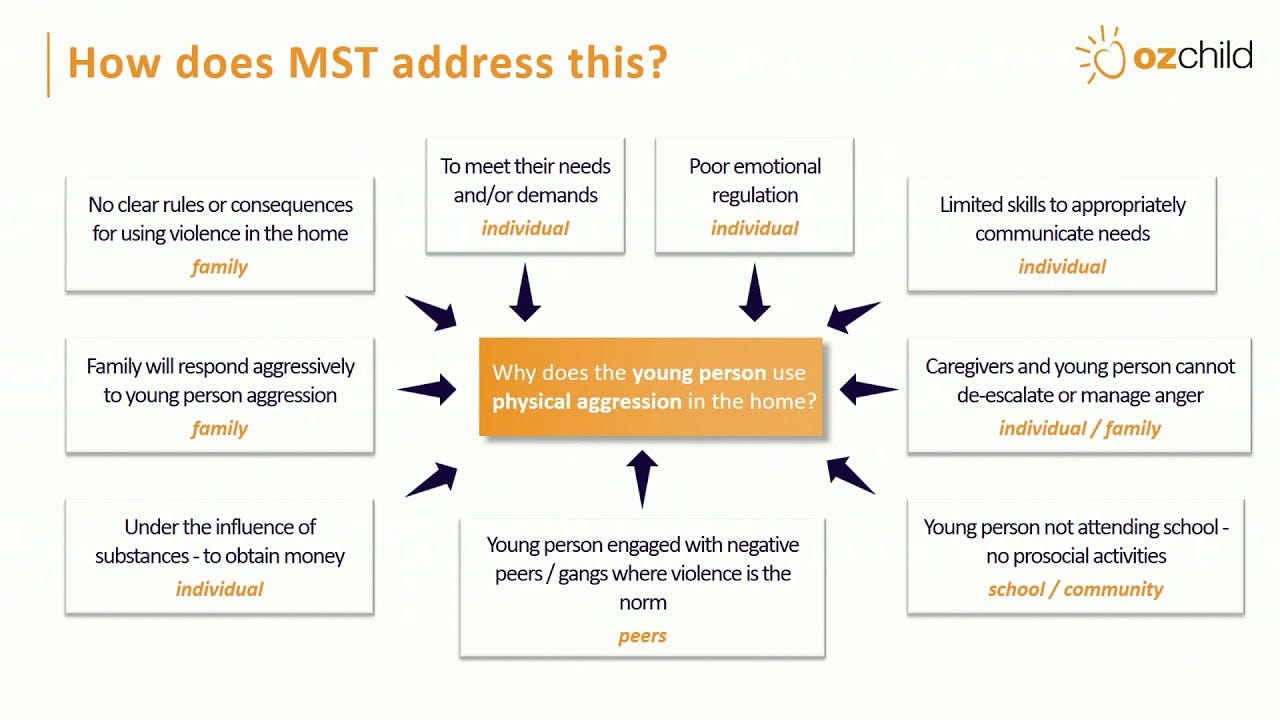

When I was a new therapist, I learned a technique for solving complex problems. I was part of a specialized clinical team that worked with the families of delinquent teens. Our therapy, called Multi-Systemic Therapy [MST], always started with a thorough assessment using a graphical tool called a “fit circle.”

To give you an idea of how it worked, I pulled this example of a fit circle off the web. Although this fit circle uses boxes instead of circles, the graphic effectively demonstrates the utility of the tool. In this example, notice how factors from various domains (individual, family, peer, school) form a perfect storm where the problem behavior [physical aggression] seems almost inevitable.

We called the boxes around the center circle “Drivers” of the problem behavior. We assumed that if we changed the drivers, the problem behavior would also change. We used specific rules of thumb to help us select the best driver. For example, clinical supervisors would often ask, “What will give us the biggest bang for the buck?” or “Which driver is most amenable to change?” or “In the sequence of change, which factor needs to be addressed before the other ones can be addressed?”

Most importantly, we were instructed to choose drivers that were “proximal” to the specific problem. For example, if a child was aggressive at school, we would focus on the drivers at the school and, even more specifically, on the drivers that occurred 5-20 minutes before the tantrum.

The smart MST clinician never chose to target stigma as a driver. Stigma is not proximal enough; nor is it amenable to change. Imagine trying to prevent a teenager from engaging in her regular habit of sneaking out of the house at night to get high with her delinquent peers. You could argue that stigma has made her stop taking her psych-meds at night, which leads to her not sleeping. Or you might argue that she can’t make friends with less delinquent teens—the kind that don’t entice her to sneak out every night—because well-adjusted teens reject her due to her mental illness. Those things might be true.

But, it’s wiser to focus on more proximal drivers of the problem, such as “ineffective monitoring by parents.” A driver like that could be addressed by plans such as “parents install an alarm on the bedroom window,” “parents perform hourly bed checks,” or “parents will take and hide shoes and jacket when child enters the house.” These are practical, proximal, and amenable to change.

Conclusion

I hope I have shown that, at the very least, the goal of destigmatization has clay feet and doesn’t deserve the unmitigated enthusiasm the government and mental health advocates have lavished on it. I agree that stigma may make life harder for some people with substance abuse or a mental illness, but eradicating stigma isn’t a panacea. Moreover, some things should be stigmatized. And even when stigma is clearly a part of a larger problem, it often makes more sense to tackle drivers that are under your control.

This is not everyone’s take on stigma. But in this Substack, I try to share from my experience as a therapist, clinical director, and chaplain. Even if readers disagree with me, I hope my posts push my readers to think— and come to their own conclusions.

If you know someone who might enjoy reading this Substack, consider sharing this publication with them.

Great post. Prepare for more demonic imprecations.