Last week, I shared the story of a road trip with Sedrick, an addict who went home to face warrants for petty crimes. Having these outstanding warrants was holding back his progress in recovery.

The last post ended at a pivotal point in the narrative. My truck blew a fuse on the way to the courthouse, which caused a 15-minute delay—a delay that almost derailed the entire trip.

Hear Ye, Hear Ye! The court is not in session.

We arrived at the parking lot of the courthouse at 1:20, five minutes after the walk-in court session began. Sitting in the passenger seat, Seddrick’s posture stiffened up: “I’ve never gone to jail sober.”

I laughed. “Yeah. It’s probably easier drunk.”

Two minutes went by in silence. I wondered if he was going to get out of the truck.

I suggested we pray, and Sedrick agreed. We took turns pleading for courage, dignity, and peace.

Sedrick got out of the truck, walked across the parking lot, and opened the door to the courthouse. Behind the door was a hallway that led to a tall counter, behind which a short and pretty Native clerk smiled at us.

It was 1:35. Twenty minutes after court started. Sedrick announced his intention to face his warrants; the clerk informed us that the judge was gone for the day.

“He’s what?” I said.

The clerk explained that the judge had concluded the court’s business and would not be returning until next week. I felt like I was in a western movie. What kind of judge conducts business for less than 20 minutes, once a week?

A huge problem

With the judge away for the week, Sedrick was left with many unanswered questions.

Should he go back to the valley, finish out the work week, and come back next week?

Could he go to the jailhouse and turn himself in?

Should he scrap this plan and try this again in a couple of months?

As we stood at the counter, Sedrick considered his options, and the Clerk made some suggestions, which included filing a motion with the court and other measures, none of which seemed to address the fundamental issue: the judge was out for the week, and the original plan wasn’t going to happen.

Eventually, Sedrick and the clerk determined that he might be able to turn himself in to the local jail. We drove 40 minutes to the middle of nowhere. The jail was an 800-square-foot dilapidated structure with a tall fence surrounding it. Sedrick told me about a friend of his who, while still drunk, decided to jump that fence and make a run for it. The decision turned out badly for him because breaking out of jail was a much bigger crime than the one for which he was in jail. He ended up getting sent to prison for a while. Short-term payoff, long-term pain.

Unfortunately, after several minutes of pushing the buzzer, we determined that not only was the jail closed, but it might be abandoned. From here, the next option was another 30-minute drive to the local police station. Would it be open? Could he turn himself in?

We were about to find out—as long as Sedrick didn’t lose his nerve. Sedrick was like a man on the edge of a high diving board; every time he worked up the courage to jump, the lifeguard asked him to wait. For somebody who doesn’t really want to take the plunge, the natural response will eventually be—cool, I’ll come back later. . . much later.

The Final Rendezvous

The police station was a very different kind of building from either the courthouse or the abandoned jailhouse. This was a modern building with manicured landscaping, large open windows, and a granite floor featuring a huge county seal. Display cases showcased cop memorabilia, and a flat-screen TV played announcements and educational content.

We waited in line to speak to a woman behind a plexiglass wall. She spoke into a microphone, and her speech was projected to the lobby via a speaker attached to the plexiglass. Sedrick had to shout into a circular metal grate in the plexiglass.

Sedrick announced his intention through the metal grate. It took a few minutes for the woman behind the counter to retrieve Sedrick’s information. It seemed like maybe we had guessed wrong about this being a place for Sedrick to turn himself in.

But, after punching some keys on her computer and consulting with the other front desk lady, she told us to wait for the officers to come out of the doors to her left. I felt a little of Sedrick’s nerves, as he stood straight up and rocked from one foot to the other.

Within minutes, two police officers approached Sedrick calmly. Their uniforms included bulletproof vests, badges, radios with mouthpieces attached to their shirts near the shoulders, guns, pepper sprays, nightsticks, handcuffs, and other equipment. They were both hulking specimens, and one towered several inches above Sedrick.

“Hey, Sedrick. What’s going on?”

“Well, I have some outstanding warrants. And I’ve been in recovery for over two years now, and it is time to make amends for what I’ve done.”

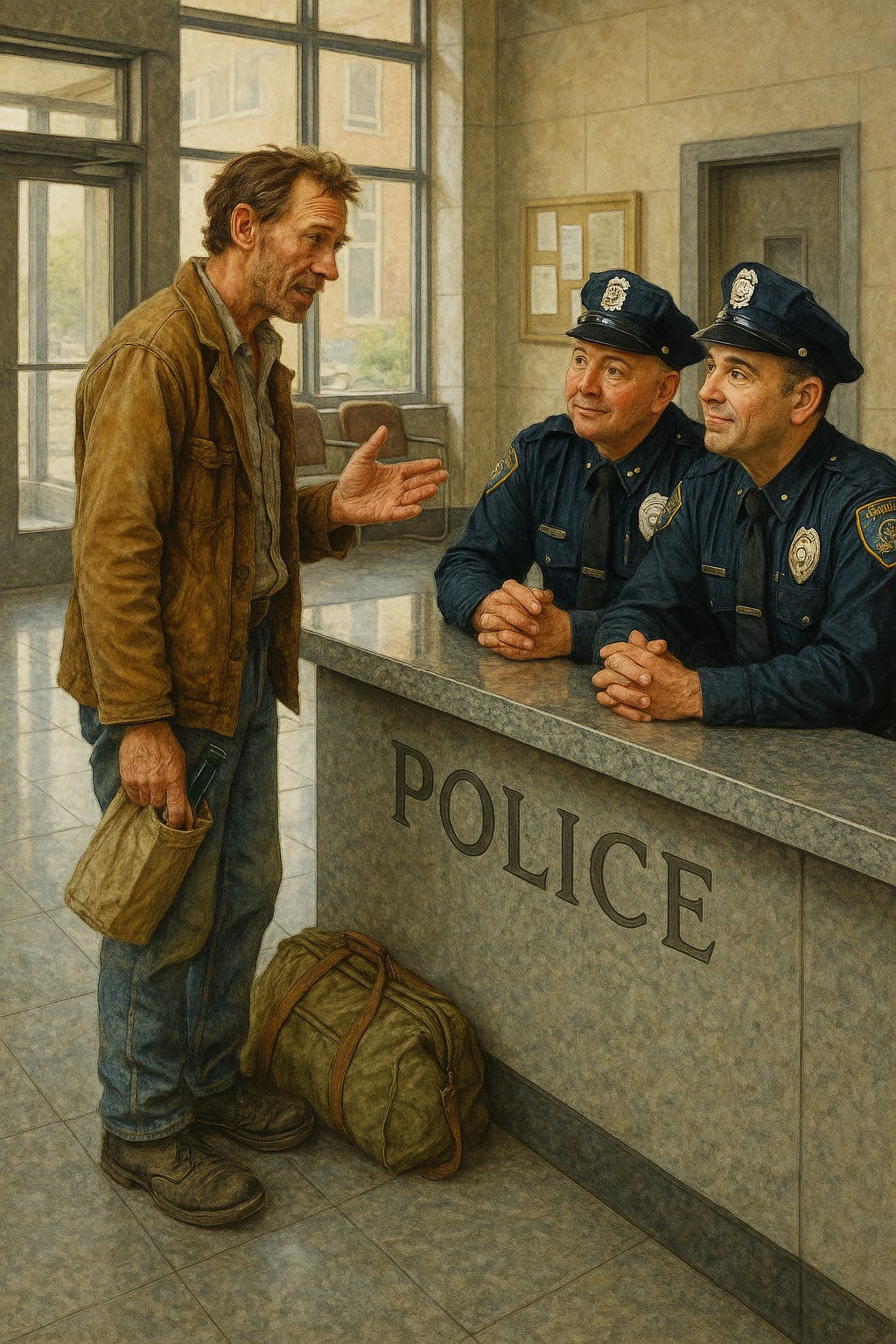

If Norman Rockwell were still around, he could paint the scene and convey the stiff dignity and courage. I did this image with ChatGPT, it’s a little too quaint. You’d have to update the uniforms, make the cops look more like Marines. And make the reformed alcoholic Native and, less beleaguered. Sedrick is actually in good physical shape from working outdoors.

I was immediately overcome. I turned away. No reason for Sedrick or the cops to see my face at that moment. But I can tell you felt proud. I felt like a father. I felt like my son was being honored for military service, or he was in the final stages of earning his Eagle Scout designation.

I know. I am not his father. And I know it’s unseemly of me to bask in the glory of this moment. But he asked me to drive him there. And I was able to be there. So, it’s not exactly stolen valor; it’s more like I was caught up in the moment. You’ll have to pardon the frog in my throat.

I turned back around to see the police officers nod their heads up and down. But it wasn’t an ordinary “Ok, I acknowledge what you are saying” nod. It was more like they were striking an accord; it was them saying, “This is good what you are doing, and I respect you for getting clean and getting to this point.”

The shorter officer said, “You don’t remember me, Sedrick.” I noticed that he used his first name. “But, I arrested you a few times back in [Sedrick’s hometown].” He nodded again. And this is going to sound like B.S., but I think he nodded like he was saying, “I love you, man. And even back then, I was hoping to see you have a day like this.”

The Green Mile

The rest of what happened was procedural, but respectful. The officers announced each step before enacting it. They were going to search his pockets. Yes, he could give his wallet to me. No, the vape couldn’t go into storage. Yes, he could take the socks and underwear he bought for this occasion. Now, they had to look around his belt and at his ankles. They were going to lift up his shirt. They were going to put the cuffs on now. They were going to walk outside and around to the detention entrance. Here was a number I could call to find out his status.

Then Sedrick walked out. The door closed behind him. He and the two officers, one on each side, disappeared around the corner.

No sky going dark. No thunder. No ripping of the temple curtain. But, here was a person who, by accepting punishment, would be rewarded and who, by losing his freedom, would gain it.

Made me cry. The courage needed to continue despite the setbacks is worthy of great respect. I pray he stays strong and is able to continue walking his new path.