Prison Satisfaction Surveys

Why the much-maligned satisfaction survey is useful

When I worked in the highly secular field of psychology, satisfaction surveys were looked down upon as a specious and uncouth form of data collection. The message from funders and insurance companies was uniform:

“Who cares if patients LIKE your program? We want to know if it HELPS them.”

I get their point. Treatment providers could give patients a trip to the State Fair under the guise of “skill building” and charge taxpayers or insurance companies for mental health services when all they've done is provide entertainment. A clever Behavior Coach looking to justify their outings could document that they provided lessons in “budgeting,” “impulse management,” or “emotional regulation skills.”

If I were in the insurance company’s shoes, I’d demand some proof, too.

But, the only truly reliable method for determining whether a program works is a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT). And no one but the government or pharmaceutical companies has the money to perform an RCT.

Even implementing a program that has been proven effective through an RCT is too expensive for most mental health care providers. Most settle for what is called “evidenced-informed” treatment, meaning that practitioners approximate a treatment by gleaning what they can from research articles or watered-down training from people who may or may not be certified in the program or practice.

Satisfaction Surveys and Anecdotes

Fortunately, there can be some value in customer satisfaction surveys. For example, something Rory Southerland said about restaurants and consumer products seemed pertinent to my ministry’s situation. He mentioned that a very important thing for any business to know is whether customers RETURN.

Here’s some of what he has pointed out:

If you ask some people about their favorite restaurant experience, they may tell you about a tiny brasserie in a Romanian locale. But, if you ask them, did you ever go back? The answer is often “No.” Rory suggests a better restaurant is one that inspires—and makes possible—many return visits

Rory really likes his air fryer and is convinced air fryers will continue to be a popular kitchen item. Why? Because it is an item that people will buy again if something happens to it, whereas most people wouldn’t replace a yogurt maker or one of these pointless gadgets.

A good treatment, product, or business idea is distinguished from a poor one by how willing people are to repeat their purchase.

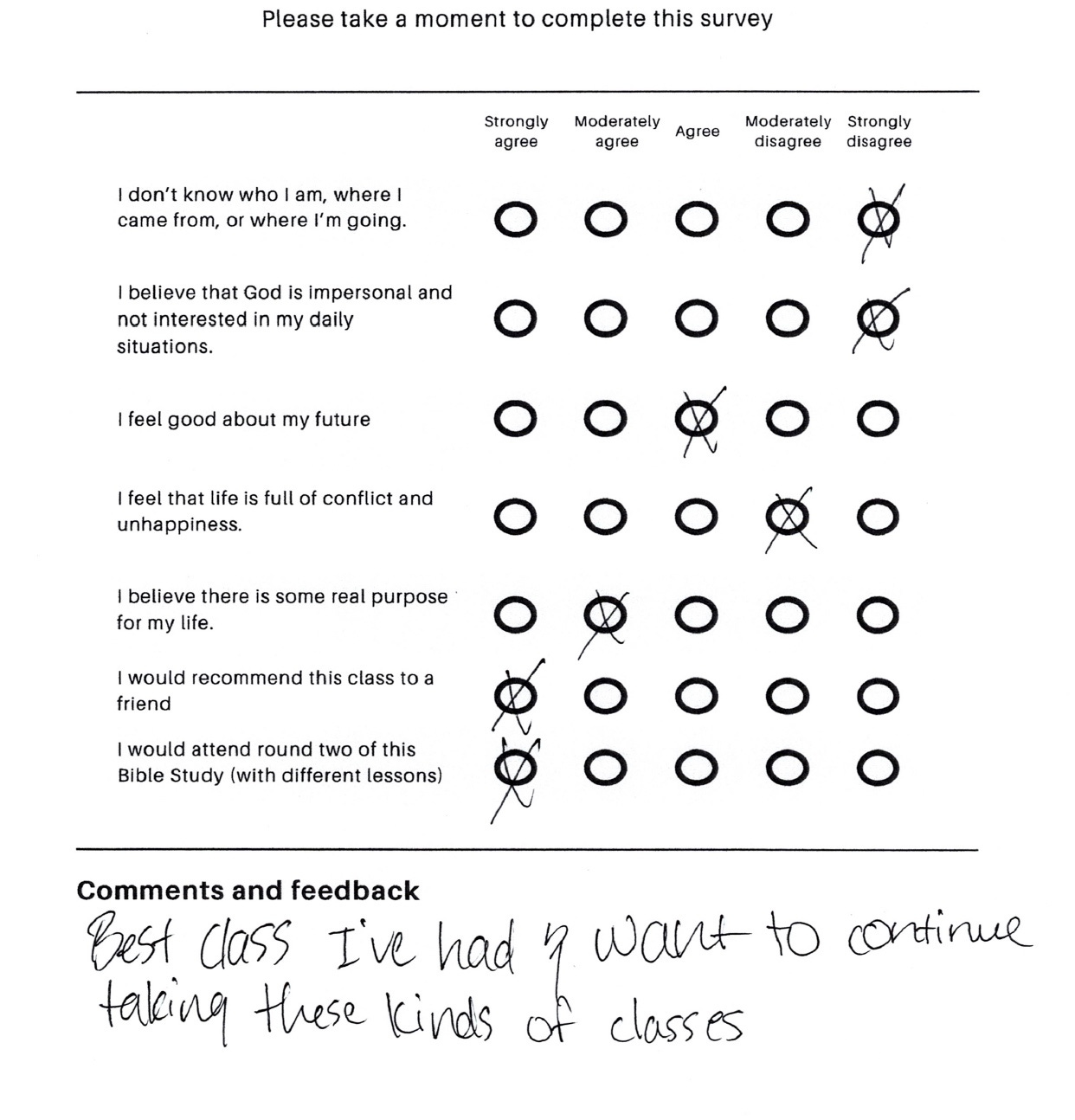

Based on Rory’s insight, I added the following statement to our post-survey, “I would attend round two of this Bible study.” The answer to this question was a unanimous “strongly agree” in every survey from my two most recent prison groups. See this representative example:

Old me—mental health manager me—might have dismissed this data point. After all, who cares if they like it? “I want to know if they are getting better!” But Rory is right. It is extremely valuable to know if people would take this course again, especially in light of statistics on the horrendous attrition rates from recovery services. (I have reported on attrition previously. Only 6 in 100 people complete a recovery service.)

I would argue that making a program people are willing to stick with is actually a very important goal. Researchers call the ability of a program to make people stick with it its “acceptability.” For example, most people won’t run a marathon, making it a very unacceptable health recommendation. But many people will take a walk after dinner. The acceptability of taking a walk after dinner makes it an intervention public health advocates will want to promote.

Moreover, by making a program acceptable, you are helping to change people’s perceptions of themselves. One woman in my latest group cried at the last session, saying she had never completed any prison program before. Completing our Bible study made her tearfully declare, “I am really different now. I am the kind of person who sticks with things.”

Completing a highly acceptable program can also build behavioral momentum. It points you toward positive change and gives you some wind at your back. This is important because most people don’t make giant leaps forward. Instead, they take what researchers call the Proximal Next Step—a logical and realistic course of action—rather than an Optimal Next Step, which may require too much effort and uncertainty. Little strokes fell great oaks, as Mr. Franklin would say.

Thus, the inmates’ response to “I would attend round two of this Bible study” is encouraging. At least we know that Resilient Recovery groups inspire repeat purchases. People think the groups are more like Rory’s beloved air fryer than an asparagus peeler or motorized ice cream cone turner. RR groups are the kind of thing you’d buy again if something happened to them.

If you would like to donate to Resilient, the repeat purchase of recovery groups, click the link.

THANK YOU FOR CONSIDERING A DONATION TO RESILIENT