How Even the White and Nerdy Can Help

On why "normies" should not be afraid to help addicts and alcoholics

“The opposite of a good idea can also be a good idea.” —Rory Southerland.

Weird Al’s spoof “White and Nerdy” is built on the assumption that people who are too vanilla will be dismissed as annoying or irrelevant by people with grittier backgrounds. The video’s central trope is poking fun at Weird Al’s character because he lacks street cred. I have to admit there are times I relate a little too much to this video. Conventional wisdom tells us we need street cred if we want to help prisoners or addicts.

Addicts and alcoholics sometimes contribute to this unhelpful perception by saying things like “Only an addict can help another addict.” Of course, they aren’t wrong, per se. The truism emerged because early recoverers found that fellow addicts offered something precious—the assurance of ‘you’re not uniquely broken’. And if you think about it, who wouldn’t want help from someone who experienced recovery firsthand rather than from someone with mostly book knowledge of how recovery is supposed to work?

But in today’s post, I want to explain why the opposite of the statement “only an addict can help another addict” is also a good idea. In addition, I’ll give you my 4-point advice on how to help addicts and prisoners, even if you’re white and nerdy.

But First: The Origin Problem

Walk with me here. I want to help you see the problem with the “only an addict. . .” dogma. If only an addict can help another addict, then how did the first addict ever get help? Presumably, there must have been a First Addict—an Original Recoverer—who became sober and was then able to help the Deputy Recoverer, who then helped a third, who helped a fourth, and so on, creating a lineage of recoverers all the way down through history to those who are now engaged in helping the current batch of addicts get sober.

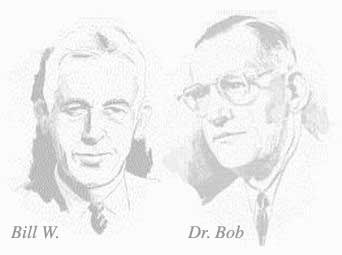

According to the AA origin story, Bill W. and Dr. Bob were the Original Recoverers back in the 1930s. Before they found the solution, alcoholics had no hope.

But the idea of a First Recoverer isn’t plausible. Nor does it seem likely that individuals in the 1930s were the first in human history to unlock the secret of sobriety. In fact, the New Testament tells us that “drunkards” were being transformed as early as the first century. So the time stamp on “the solution” needs to be adjusted by a couple of millennia, at least.

As far as a First Recoverer goes, the truth is it often takes a community of helpers to achieve sobriety. In that community, some might be former users; others might not be. Each group has its own strengths.

So if you need someone with firsthand experience with quitting, talk to a former addict. The same goes for finding someone to take your desperate 3:00 AM phone calls. But, if you want to get the opinion of a Sobriety Native—someone whose approach to life is untainted by what 12-steppers call “Stinking Thinking”—you might want to talk to someone who, from the get-go, has handled life’s vagaries sans alcohol.

My friend Verdell says as much about Resilient Recovery meetings, “If this is where the leaders of the church share how they think about and manage problems, this is where I need to be. The only way I know how to manage problems is to drink.” He wants to learn sobriety from the never-addicted. Not a bad plan, in my opinion.

Yet the insecurity continues

I’ve been taking two female volunteers with me to the prison to conduct Resilient Bible studies. After their first visit, they seemed to feel inadequate. “What do you think they thought of us?” they asked me. They seemed disquieted by a version of “only an addict...” which told them they needed to have been incarcerated to be helpful to the women in prison.

One of the volunteers mentioned she had “only” been addicted to alcohol and weed, and thus, felt like she would be dismissed by the inmates for being a lightweight. The other volunteer had experience with street drugs, but had not been to prison. She also felt unfit for service.

My encouragement was to look at me. I am a straight, white male. Never incarcerated. Over-educated. Grammatically [mostly] accurate. I am a person who benefited from a private Christian education and who grew up in a neighborhood so safe and stable that we literally didn’t have a house key because there was no need to lock our doors. Sure, my dad said some pretty mean stuff to me growing up, but any parental mishandling I experienced is laughably minor compared to the jaw-dropping, multi-generational patterns of addiction, instability, domestic violence, and sexual assaults that are common among the prison population. Heck. I am such a square, I wear a long-sleeved, collared shirt to do yard work.

And yet, the whitest, malest, most mid-western, middle-class, middle-brow, milque toast of a human imaginable gives one of the most popular classes in a female prison. My relative popularity in prison doesn’t come from my street cred or the stupifying amount of alcohol and immaturity in my past: It actually stems from my plain Calvinist upbringing and sensibilities.

What, then, should we do?

What makes the truism “Only an addict can help another addict” wrong is only the word only. Sure. An addict can help another addict. But when it comes to recovery, the opposite of an addict can also help an addict. Thus, judges, teachers, nurses, butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers should all be welcome advisors and supporters.

That said, I do have some general guidelines for sober people wishing to work with people in recovery.

Avoid comparing experiences. You’ll hear things that will make you feel grateful—or even guilty for the grace you’ve had in life. But, even if there are substantial differences between you and those you hope to serve, there’s no need to point out the differences. Comparison of struggles can become a barrier. It can easily be interpreted as a humble brag.

Don’t avoid sharing struggles. Rather than comparing or noticing differences in experiences, simply share your struggles when appropriate. Just be you—unapologetically and without self-consciousness. Your struggles—as light as they may seem by comparison—will often provide a surprising sense of relief to an addict. More than once, I’ve heard an addict say about a “normie”, “I thought your life was perfect! Maybe I am not so messed up after all.”

Avoid pandering. Don’t change the way you speak, dress, or act to fit in. Remember Mr. Rogers? Think about that man for a second. Not an ounce of street cred, and as unfamiliar with ghetto etiquette as a person could be. Yet he was cherished by millions of inner-city latch-key kids. His warmth and emotional intelligence counted more than his similarity to his audience.

If you’re funny, be funny. If you’re not, this isn’t the place to start. But if you can quip, joust, parry, or jab with humor, it’s greatly appreciated. In prison, sarcasm, irony, and deadpan comebacks are a form of entertainment and worth more than cigarettes and Honey Buns.

The bottom line is just be comfortable. Be yourself. Remember, the point of ministering to people isn’t to grace them with you, wonderful you! So there’s no pressure to be anything you aren’t. My pastor’s prayer before each sermon is applicable here: Lord, if I make a fool of myself, may it point them to you.

Ultimately, the comfort we give isn’t ours. It doesn’t come from us. It’s not about us.

3 Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort, 4 who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God.

I’m white and nerdy too, but Jesus still loves me. 😇