A Tale of Two Prison Yards

The amazing power of context to make or break a visit with a chaplain

In his book Alchemy, Rory Southerland talks about the importance of context. Context often can’t be quantified, and thus, it is ignored by many. In the world of recovery, context is often dismissed as fluff or coddling. In this post, I examine how context can make or break a recovery experience.

Last week, I interviewed inmates for Resilient Groups, hoping to weed out anyone who is a bad fit for our program. Typically, this is a pretty straightforward enterprise. But this time around, things didn’t go as I expected.

In one yard, inmates were out of control, and two inmates nearly got into a fight. In the other yard, the inmates were vulnerable and reflective—some were tearful.

Now, these are two very different yards. Yard One is a higher level of custody, so the inmates are generally younger, angrier, and have more facial tattoos. This was the yard where the fight nearly broke out.

However, the differences in the populations of the two yards do not account for the stark contrast in their attitudes and behaviors. Context does.

It was the worst of yards

In Yard One is a locked yard, which means that I would have to unlock the gate and escort each inmate, one by one, back to the chaplain's office. The time spent walking would have been almost equal to the interview itself—and walking back to the chaplain’s office with a stranger would be very awkward for most inmates.

So, I interviewed people on the yard itself, sitting at at a concrete picnic bench far away from the other inmates, hoping that would give us a little privacy. It didn’t. Inmates crowded around the picnic bench as soon as the chaplain’s clerk [who is herself an inmate] called them from their cells. One line formed on my right, and another on my left. The inhabitants of each line kept reminding the others who arrived first and who was next.

While interviewing one inmate, another stormed over and began challenging her. “Why is my name in your mouth!?” This is prison slang for, “I heard that you are recounting falsehoods about me, and I find it distressing.”

This was not my first front-row seat to a female fight. So, I did what I normally do. Sigh heavily and take a step back. The sigh serves two functions. It serves to communicate that I find the matter boring and won’t be triangulated into it, and it also gives me a minute to spot the nearest guard in case I have to alert them. Fortunately, this little spat fizzled out quickly, and no real harm was done.

Still, the interview process was lousy overall.

It was the best of yards

Fortunately, Yard Two was an entirely different experience. On this yard, inmates can walk to the chaplain’s office without an escort. A guard whose office is next to mine simply radios the guards near the cells and asks them to send the inmates to me. Inmates arrive in clumps of two or three and sign in with the Chaplain’s clerk. They sat on chairs outside the office while I interviewed each inmate individually.

The chaplain’s office is tiny—sort of like Harry Potter’s room under stairs at his uncle and aunt’s house.

Ok. Maybe it’s not that small. I went back and forth with ChatGPT to make this image of the office.

ChatGPT got close. The actual office is about a foot narrower. The desk needs to come forward, and a plastic chair needs to be placed under the window with its back to the wall. Also, the chaplain’s chair isn’t a metal folding chair with impossible geometry. [Sheesh, AI, were you studying M.C. Escher drawings when you came up with that chair?]

The windows are also much clearer. You can see in and out as plain as day.

But the point is that this office—poor and pathetic—was a small change in context that transformed the interview process from schoolyard chaos to something akin to the sanctity of a priest’s confessional. Along with the office came a tiny bit of privacy, an orderly sign-in process with the chaplain’s clerk, and a waiting area where people’s place in line was honored

The change was remarkable.

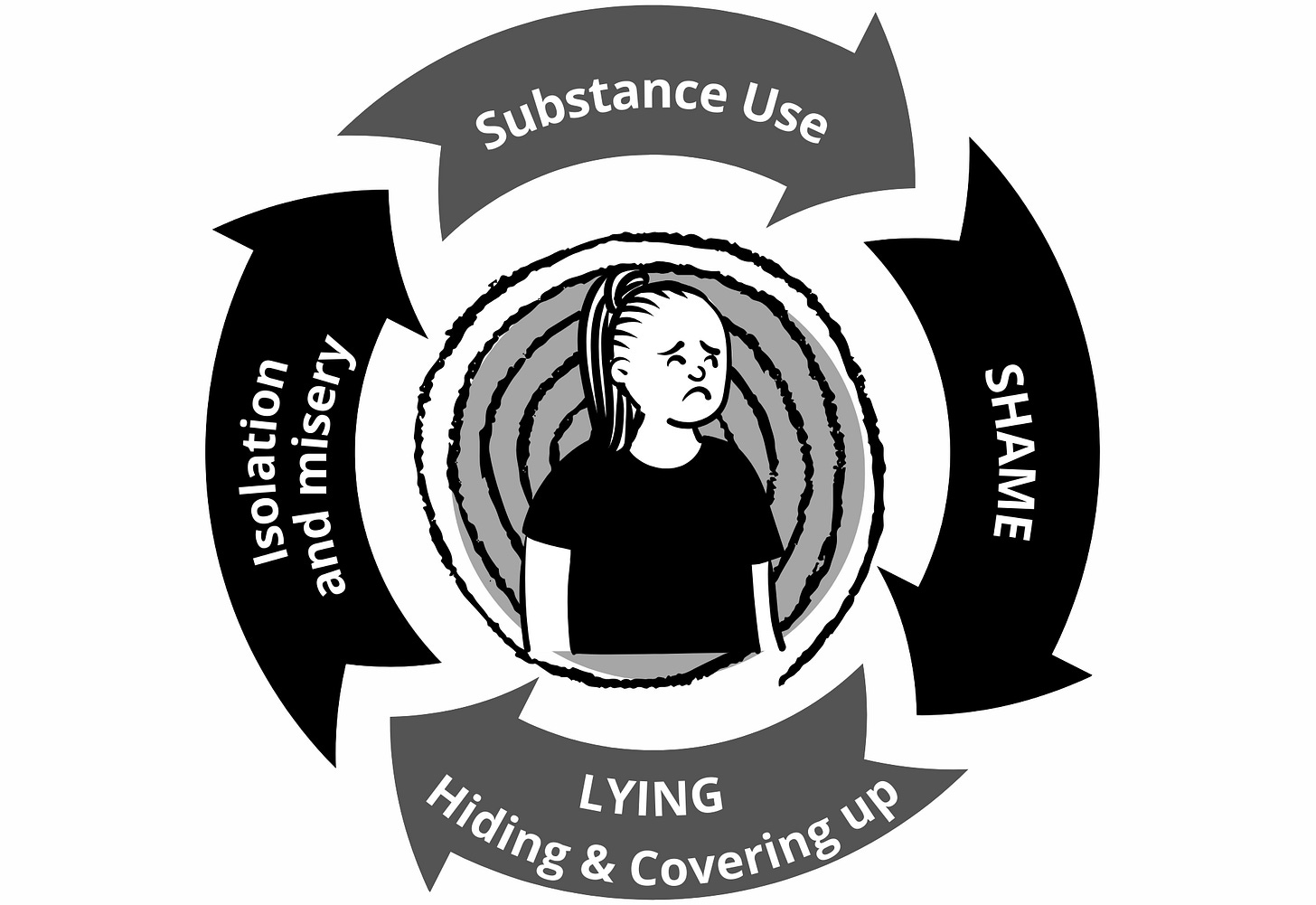

After I introduced myself and shared a little about my addiction, the inmates opened up about theirs. That was nice. Then, I explained this little diagram. I gave a few examples of how substance use leads to shame: “Having the label of addict; the things we do when drunk or high; the things we do to get the substances; and the things that we fail to do because of our addiction. . . these are things that cause a lot of shame.” Fully a third of the inmates teared up when I gave my spiel. One inmate began crying as soon as I said the word “shame” for the first time.

I am not suggesting that tears equate to life change. They don’t. But, I do think it is interesting how small changes in the context greatly influence people’s behavior and attitudes. In both yards, interviews were completed, and pre-program surveys were filled out. In a research paper, the feeling and vibe of the meeting would extracted and some cold, factual sentences would be given:

In Yard One, inmates were interviewed on the yard due to custody restrictions. In Yard Two, inmates were interviewed in the chaplain’s office. 48 inmates met the requirements for the program, and 12 from each yard were randomly assigned to receive the program.

But Yard One’s sense of expectation and hope wasn’t improved. In fact, it may have been lowered. Nothing about the interview helped them get into a helpful mindset for the program.

Inmates on Yard Two, on the other hand, left feeling elated. They thought the program made sense, and their trust in me as a leader was solidified. They were excited to get started.

It is possible, but unlikely, that a research paper would discuss the differences in context in the discussion portion of the paper. Because demographic data would be available and quantifiable, it is much more likely that the demographic differences would be cited as potential reasons why the outcomes of the two groups differed, leading to a couple of lines in the paper that would read like this:

Inmates on the High Custody Yard were younger, more racially diverse, and were more likely to have committed a violent felony. The results of this study suggest that inmates on High Custody yards may need more sessions or additional services.

The lesson, please

Too often, those of us in the recovery community take a mercenary approach to the context of the programs. If the walls need paint and the parking lot feels sketchy, we tell ourselves, “It’s OK. This is authentic. Don’t want to make the place too fancy or our people won’t feel comfortable.”

But I think this is wrong.

Anyone entering a program wonders, “Is this place legit?” We hate uncertainty and don’t want to be taken advantage of by a worthless program. Cues in the context convey a message. Either this is a trustworthy and caring place, or it is a fly-by-night operation where dreams of sobriety go to die. We decide how much faith and energy to invest in a program based on subtle, difficult-to-quantify contextual information.

But rough-edged places have street cred and authenticity, right?

Many people argue that a rough-edged, impoverished program is somehow better than one with money but no heart. It’s what we might call the Local Pizzeria Theory. It’s true that a lot of really great pizzas—or tacos—come from hole-in-the-wall outfits that don’t look slick and fancy.

But there are also disgusting pizza—and taco— places that will make you sick. We are highly tuned instruments when it comes to telling the difference between a great neighborhood pizzeria and a dispensary of dysentery.

In pizza shops or recovery programs, there are certain corners you just can’t cut. In the pizza industry, the pie has to be good and safe to eat. Quality ingredients, the right stove, and a good pizza chef are indispensable.

In the world of recovery, there are things you can’t skimp on—and things that must be top-notch.

I’m curious if my readers have had experiences in which the context of a recovery program encouraged them to feel hopeful or left them feeling a little uncertain about the ability of the place or program to help.