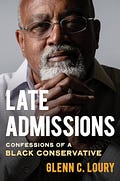

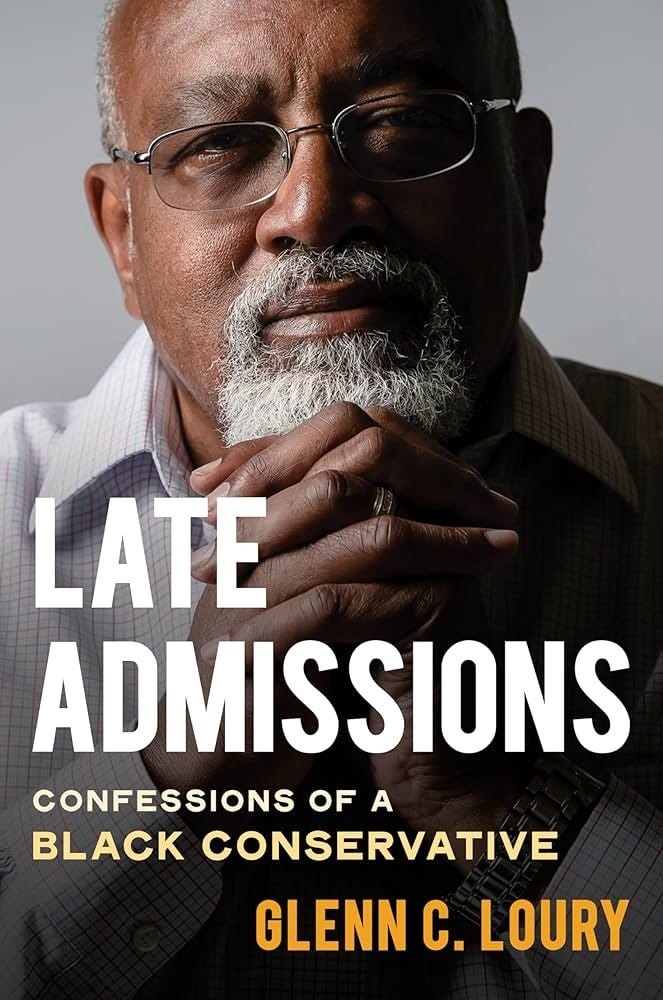

Glenn Loury's Memoir: Economics, Race, Religion, and Crack Cocaine

A semi-review of Glenn Loury's memoir: "Late Admissions".

I’ve been waiting for the publication of Glenn Loury’s memoir for months. He is a complex guy whose story spans from his humble beginnings on Chicago’s Southside to his ascension to the heights of academia as a Harvard Economics professor. At various points has been a Black radical, a Reagan-era NeoCon, a born-again Christian, a pool hustler, a family man, a philanderer, and a crack addict.

Apart from being fascinated by his story, I was also interested in what his prose would be like. Based on his odd-couple podcast with linguist John McWhorter, I guessed it would be good. I find myself laughing out loud at Glenn’s acrobatic rants against those he calls “the race-hustling, three-named people.” [I’ll leave you to decide who those people might be.] I don’t always laugh because I agree with him, but I admire the sheer agility of his verbal takedowns. The angrier he becomes, the sharper his thoughts and verbal prowess seem to get. Listening to his rants is like watching a clever magic trick—it's so surprising and skillful you laugh without meaning to and then wish you could know the secret so you could do it, too.

I was also interested in seeing what he could teach me about recovery.

And Glenn did not disappoint.

His descriptions of his youth and childhood took me into the postwar living rooms, schools, job sites, and pool halls of Chicago’s Southside. He painted rich scenes that I was glad to experience. His descriptions and anecdotes kept me returning to the [Audio] book whenever it was available. Sometimes, he told the story of his late-night carousing around Boston; other times, he described his economics papers or his collaborations with other world-class economists. But regardless of the topic, he remained an accessible and interesting storyteller.

His description of his confession at an AA meeting is typical of his wit, self-examination, and insight. The background to the confession is this: After his wife’s miscarriage, Glenn affected a sad demeanor because he knew it was expected of him as a dutiful husband. But that was, in Glenn’s words, “a cover story.” The real story was that he was relieved. A newborn in the house would have curtailed his philandering.

“I was so enamored of my own entitlement [to have extramarital affairs] that I was secretly pleased that it could continue unimpeded.”

After sharing his confession with the reader, he reflects upon what is wonderful and limiting about AA. How much he can say in just a few short paragraphs is impressive. Toward the end of the section, he hints at the necessity of religion to cure that which ailed him. Read to the end. It’s well worth it.

“One of the cardinal rules of AA is that no one is to render moral judgment on anyone else sharing at a meeting no matter how reprehensibly they’ve acted. So no one told me I was bad person. No one told me I should be ashamed of myself. No one told me how selfish I was. They just reiterated that the most important thing was not to drink—or in my case—not to smoke crack.

I understood the utility of that rule. If people feel they’ll be judged for their actions, they’ll be inclined not to share them, even if they want desperately to unburden themselves. The addict will then keep his shameful secret to himself and it will continue to feed the self-loathing, which for many addicts, is at the source of addiction. “Secrets make you sick,” is the way they put it in the recovery community.

AA meetings provide a place where these secrets can be shared in the hope that unburdening can take the place of drinking. No doubt this is a necessary process. It was necessary for me. But at the same time, I was finding AAs monomaniacal focus on sobriety— to the exclusion of all other values —to be unsatisfying.

My life as an addict not only became, “unmanageble,” [as AA would say it]— it became undignified.

AA could help keep me sober. But it could not provide a foundation upon which to rebuild the moral structures I had demolished. Sobriety was necessary, but insufficient for that reconstruction. I came to believe that for such a daunting project, I would need more sturdy materials.

I want to examine this passage in detail in next week's post. It says volumes about addiction and recovery—and humanity in general. It’s worth a deeper dive into what it can teach us about good and evil, and the human and divine.